THE STORY

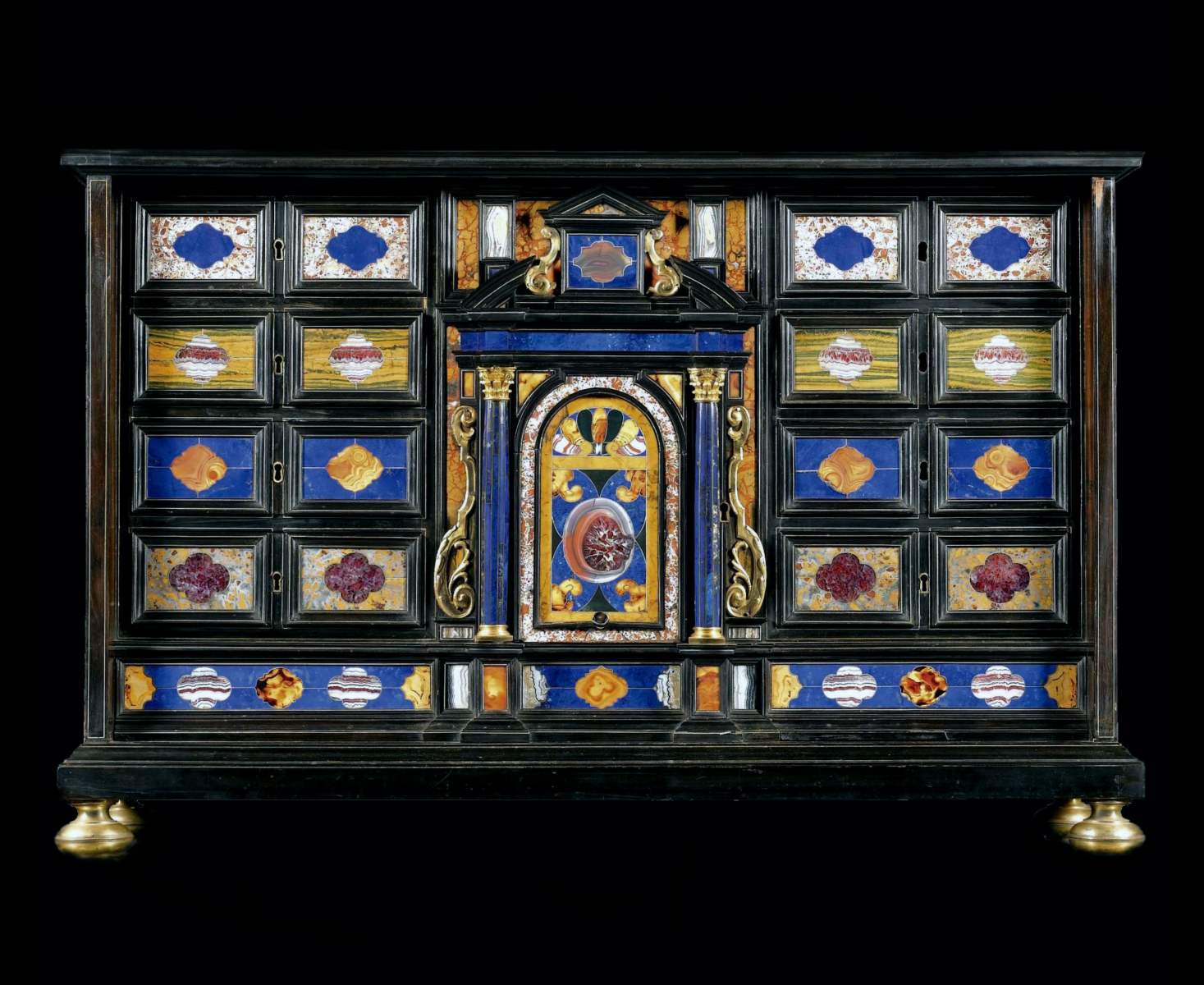

The Cabinet can be defined as a preciously produced container with drawers and compartments, used to store equally rare and precious objects, important private papers and secret documents. It has always been present in the most sophisticated and opulent interiors and has played a part on special and solemn occasions, political and religious.

Its origins go back to Ancient Egypt. In 1922 in Tutankhamun’s Tomb more than thirty richly decorated Cabinets and caskets containing his most precious possessions were discovered. The genesis of the Cabinet is inscribed in Western history from Classical times to Byzantium, and the Middle Ages. Its form evolved as did its use reflected in the various names it assumed through the passing of time. Thus Armarium, hence armoire in French, a wardrobe or cupboard with shelves and drawers, in Italian Cassone to keep the bride’s dowry and Stipo.